|

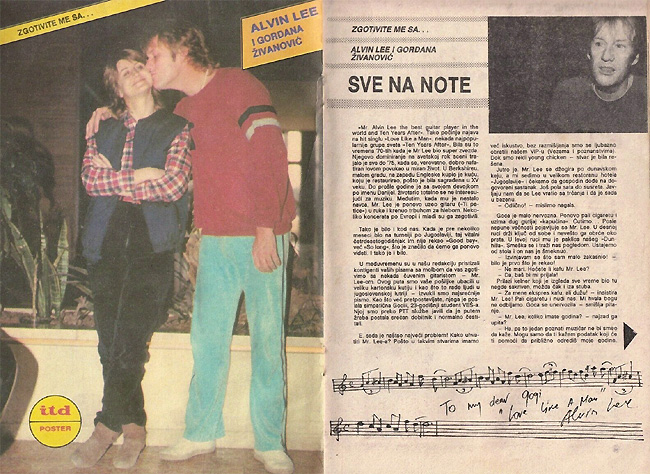

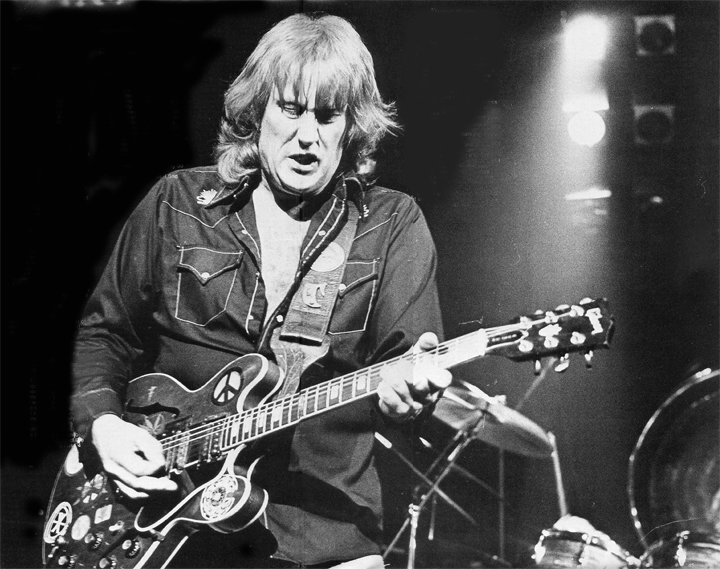

29 January 1983 -

Sportcsarnok, Budapest, published in Világ ifjúsága Magazine,

Hungary

|

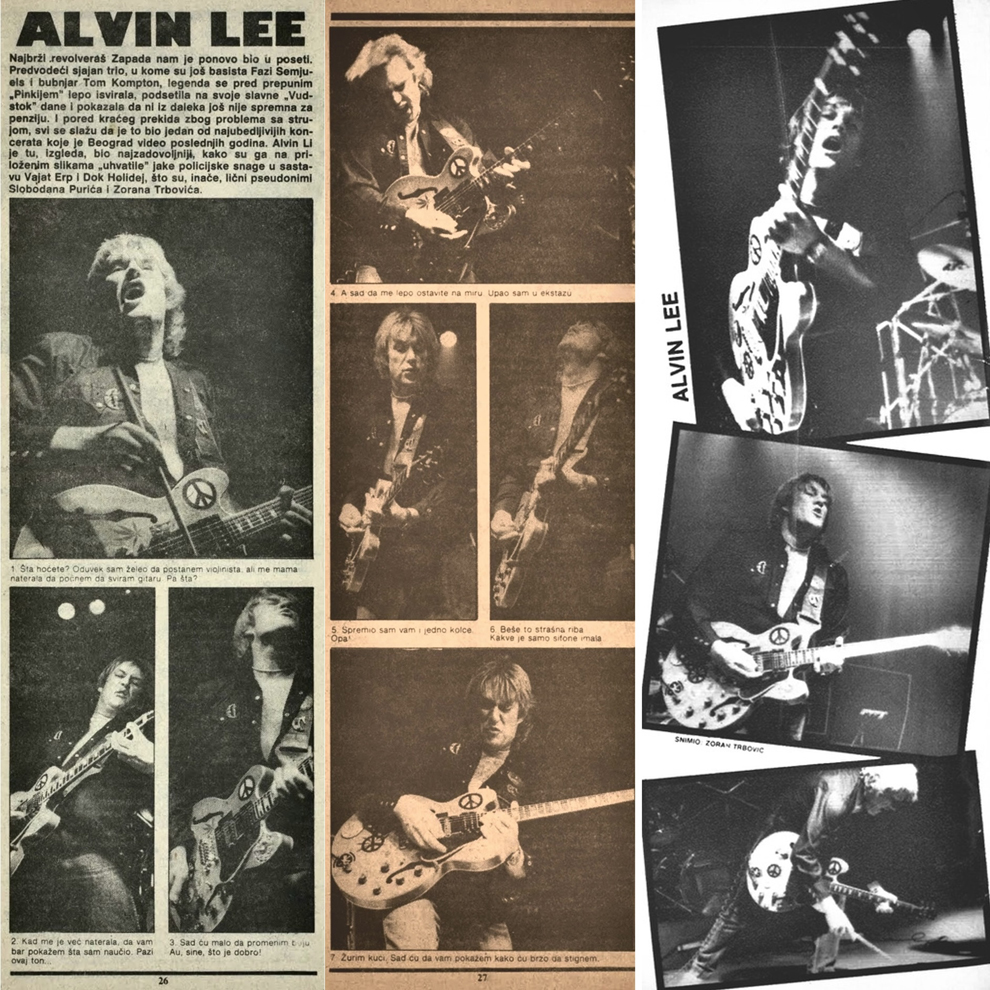

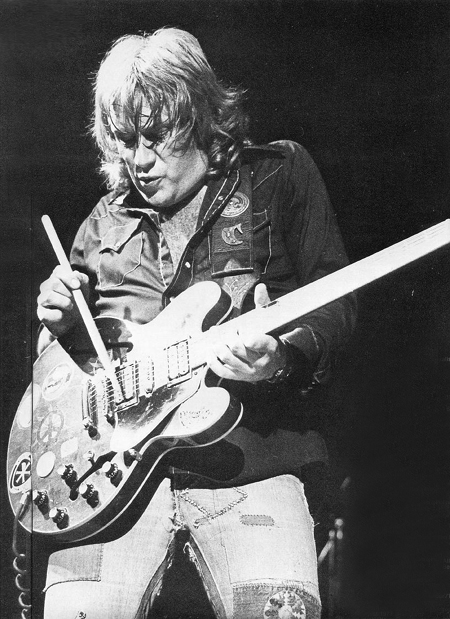

January 1983 - Alvin Lee in

Yugoslavia

Photos: Zoran Trbovic

1983 - itd magazine,

Yugoslavia

|

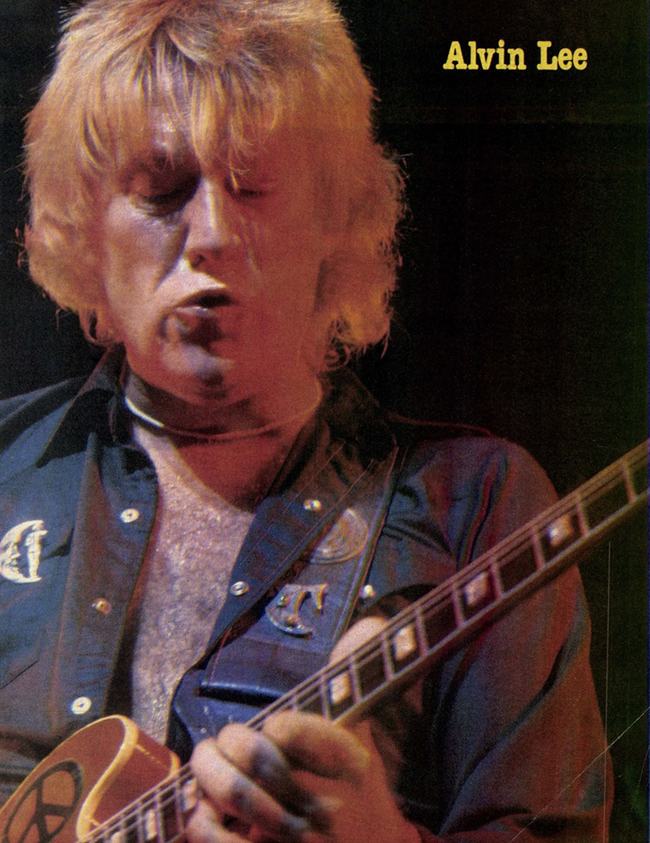

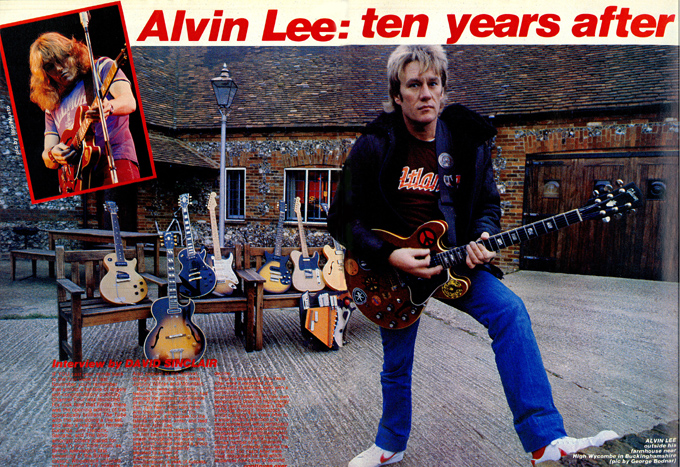

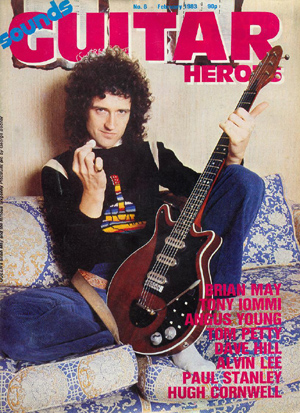

SOUNDS

GUITAR HEROES – SPECIAL EDITION

FEBRUARY - 1983 –

ALVIN LEE

Interview

by David Sinclair

If

you cast your minds back to the first week of last

November you’ll remember that amidst a fanfare of

largely self-congratulatory publicity, Channel Four was

launched. For rock fans that Friday there was the

opening edition of the sporadically brilliant The Tube

with the Jam doing a live set, and later a real guitar

hero’s bonanza. Jimi Hendrix, Santana, and The Who

amongst others jostled for space

in your front room, as British television’s

first screening of the Sixties classic, Woodstock

unfurled on the nation’s T.V. screens.

Also

present at the festival, though not in the film, were

Johnny Winter and Leslie West Mountain. But there was

one guitarist featured for whom

Woodstock had perhaps

the greatest significance of all. For eleven

minutes in the film, Ten Years After held forth with

their epic version of “I’m Going Home” a showcase

for the talents of vocalist, writer, and guitarist Alvin

Lee.

After

its general release in 1970, the film became a box

office smash throughout the world, and Alvin Lee found

himself leading a group that had become instantly

elevated to a level of superstardom. It was

simultaneously a peak of success, and the start of the

group’s decline.

Prior

to Woodstock, Ten Years After were a respected and

successful blues / rock band with a particularly

pleasing habit of occasionally dabbling in their own

personalized brand of high-energy swing jazz, such as

– Woody Herman’s “Woodchoppers Ball” and “I

May Be Wrong, But I Won’t Be Wrong Always”.

Woodstock, whilst bringing Ten Years After to a wider

public’s attention in a most spectacular way,

particularly Stateside, also disproportionately

emphasised one particular aspect of the band. “I’m

Going Home,” the climax number of an otherwise varied

set of material, became the style that Ten Years After

were most recognized for and which audiences now came to

demand. A twelve bar Rhythm and Blues shuffle / boogie

workout. “I’m Going Home” was notable for the

incredible velocity of Lee’s guitar playing. The

lyrics were throwaway to say the least, the keyboards

inaudible, drums and bass providing a monolithic thump

behind Alvin’s awesome Gibson guitar. Notes flew like

supersonic laser flashes as whole sequences passed in

the blink of an eye, and Alvin Lee stood there stage

centre, the quintessence of Rock and Roll cool.

His

features looked as if caved from granite, high

cheekbones, perfect skin, and sneering down-turned mouth,

all framed by a shock of thick blonde hair. He looked

like an ideal of Caucasian manhood, eminently photogenic

and totally confident in his mastery of his chosen craft,

but then, he’d had a fair old while to develop his

skill.

Alvin

Lee was born in Nottingham, England on December 19,

1944. His father Sam, owned an extensive collection of

blues records, and both his parents played the guitar.

So there was always an instrument laying around the

house. However, young Alvin’s first musical endeavours

were pursued on the clarinet, an instrument which his

brother-in-law- played.

After

a years lessons, Alvin swapped his clarinet for Broadway

Plectrum Guitar, and took chord lessons. His earliest

influences were the old jazz musicians, Django Reinhardt

and Benny Goodman’s guitarist Charlie Christian, but

it was Rock and Roll that was starting to percolate

through. “I was very into Chuck Berry and Scotty

Moore, who was Elvis’s guitar player,

and Jerry Lee Lewis, all straight rock and roll.

I still like it the best now. I did practice about four

hours a day, and when I was eighteen, I hocked myself up

to the eyeballs for my first electric guitar, it was a

Guy-a-tone with crystal pick-ups. Later on I got a Burns

Tri-Sonic which was awful, and then I got a Grimshaw,

which was

the nearest thing that I could afford to Chuck Berry’s

Blonde Gibson. I had that right up until the time that I

bought my Gibson ES-335 which I still use today.”

His

first group, featured the Guyatone guitar, was Alan

Upton and the Jailbreakers. Upton was a Jerry Lee Lewis

style pianist, and they played the local pubs on the

weekends. Then, in 1964 Alvin teamed up with bassist Leo

Lyons, and drummer Pete Evens, to form The JayBirds.

Pete Evens was later replaced by Dave Quickmire, and for

awhile The Jaybirds featured vocalist Farren Christy.

However Christy dropped out just prior to the group going

to play for six weeks at the Star Club in Hamburg,

Germany.

"The

singer dropped out and I just voluntarily became the

singer. I was underage at the time, and had to lie my

way in, but it was good experience for me. It was like

getting a years training crushed into a six week period.

Albert

Lee was there. Around the corner, playing at “The Top

Ten”. He could play the “Hound Dog” solo which had

always eluded me, so I introduced myself and got it

off”.

By

1967, Alvin Lee and Leo Lyons had teamed up with drummer

Ric Lee (who is no relation to Alvin Lee) – along with

keyboard player Chick Churchill, to form Ten Years

After.

The

group came riding in on the crest of the blues boom wave.

(Alvin was now in his element) “Thanks in part to my

father’s record collection, I suddenly found that I

had this great repertoire of blues songs, that

previously we could only perform at 3:00 in the morning,

when the clubs had emptied out”.

Decca,

in an unusual move, signed them to an albums only deal,

though singles were subsequently released, most notably

their 1970 hit from their album Cricklewood Green,

“Love

Like A Man”, which reached number ten in the British

charts. Their first album, self titled “Ten Years

After” caught the ear of American promoter, Bill

Graham, who booked them into his prestigious Fillmore

Auditoriums, and they quickly became a major concert

attraction in the States. Their albums from 1969 release

“Stonedhenge” were consistently strong sellers in

their native Britain.

“Underground”,

was a word that was bandied around at the time, and I

quite liked being “underground”. I had been through

the situation of wearing satin shirts and what have you,

doing a mini-Elvis Presley. And I realized that with the

kind of music we played, you don’t have to do that.

That was good, because it suited me to just turn up in

blue-jeans and a T-Shirt and not have to dress up and

have your hair done and things like that”.

Ten

Years After were an unpretentious but highly souped up

rock n´ roll unit. Although Leo Lyons, Chick Churchill

and Ric Lee were all admirably capable musicians, the

band’s principle appeal was in the dirty gritty voice

and high speed guitar of Alvin Lee. Emerging as

contemporaries of “Cream” (with Eric Clapton)

and “The Jimi Hendrix Experience”, Ten

Years After were cast firmly in that mould of 1960’s

groups that adhered to principles of technical

excellence and musical bravado and flash.

Alvin

Lee was in those days, an unnervingly fast guitarist,

and while he de-emphasises this important aspect now, he

was without peer in rock

guitar circles. Certainly for sheer speed, Eric

Clapton couldn’t have got near him, and it’s very

doubtful if even Jimi Hendrix could have matched Alvin

in this respect. Check: “I Woke Up This Morning”

from Ten Years After’s Ssssh album and see for

yourself, what I mean.

Alvin

says: “We used to sell a hell of a show (put on a hell

of a show). Ten Years After were specialist in blowing

people (other bands) off the stage, that was our ultimate goal – it wasn’t how

well we played, it was how well we went down, as long as

people went home, remembering that we played above all

else, then that was our motivation. Very unsubtle.”

Actually,

a lot of Alvin’s speed as a guitarist derived from his

background in jazz where ultra fast tempos are far more

commonplace than in rock, and the super-hyper- live

approach that Ten Years After utilized in their live

shows, energised themselves as well as their audiences.

According

to Alvin: “I never tried to be fast, it’s just that

when I got on stage, all the numbers sped up, then

suddenly the solo came and all of a sudden I’d think,

“Hell” I’m not going to be able to handle this,

but I’d just go for it…..”

But speed is not everything. The critical

backlash was not long in coming and particularly after

the Woodstock film was released. Alvin’s playing was

branded as “tasteless”, lacking in “finesse”

along with “excessive” – “self indulgent” and

“all haste and no taste” among other things. It

became a received wisdom that Alvin Lee, “the fastest

guitar in the west” couldn’t play subtly to save his

life. When in point of fact, Alvin Lee is one of the

most extremely versatile guitarist capable of playing

more styles of music, such as: Ragtime, through to

Classical and he was understandably and undoubtedly

affected by these snide criticisms as indicated by his

change musical direction subsequent to Ten Years After.

Woodstock

the movie was the watershed in the career of Ten Years

After – Alvin states: “It was a big break, but it

was the start of the end for the band too. Up till then

we had been playing eight to ten thousand seat venues.

After the Woodstock movie it changed drastically, almost

overnight to playing to 20,000 to 30,000 people every

night, and along with that, the quality of the gigs

dropped off as well. That’s when I’m positive that

the “Disenchantment” set in. Alvin continues:

“When a band is just starting out, in the early years,

all you really want to do is fill up your date sheet, to

keep working. Then, if and when the band finds some

success, you find that your date sheet is now full

everyday of the week. You work for maybe a year before

you come to the realization that you need some time off,

in order to write songs etc. and that’s exactly what

happened to Ten Years After.

Alvin

says: “ We just kept working and working and working,

then we had to fight just to get three weeks off and the

fun went right out of it. We didn’t feel that we were

achieving anything particularly, it was just what I came

to call “The Travelling Jukebox Syndrome”. This is

where you get on stage, plug in and away you go, and do

the same as you did the night before.

Ten

Years After did twenty eight American Tours alone. Each

one lasting about two months each, and in the end they

simply toured themselves out. Call it burn out or total

exhaustion, but that’s the fact. Their last official

album release as a band, came in 1974 with “Positive

Vibrations” and the vibrations were no where near

positive at this point. In fact, the band had already

split up long before this album was released –

although it was never officially announced in that way,

the band just stopped, and in an interview Alvin just

said, that

it was over, Ten Years After ceased to exist any longer.

Alvin

embarked on his solo career, in a direct attempt to

shake off some of the “No Subtlety” comments.

Alvin

continues: “ Some of the criticisms about me being all

flash and no taste affected me personally, but I was

pushing that side of it for a long while, and then I

started to back off a bit and I went through that whole

psychological thing of thinking, “I must do something

more tasteful just to prove it”. But overall it

didn’t do me much good in the long run, all it did was

confuse the audiences.

Thus

a collaboration with Mylon Le-Fevre

began that yielded an album called: “On

The Road To Freedom” released in 1973, which

established a more tasteful tone, that continued on

through three albums during this period. For live work,

Alvin formed a nine piece touring band: “I did a very

tasty set, that worked out very nice in clubs, but put

that into big arenas and it was frustrating to me,

because halfway through the set, and although I’d gone

off doing the unsubtle stuff, I suddenly felt that the

audience was wanting some real grating rock n´ roll.

But the way that the band and the equipment were set up,

we really couldn’t deliver grating rock. I was going

through the fifteen watt WEM only, miked up and coming

through the monitors – it’s a totally different feel

to having four cabinets behind you.”

Alvin

was grapping with the problem that faced all of the

sixties guitar-axe heroes: how to move forward into the

seventies without disappointing audiences who know you

for one particular body of work, that’s rooted in the

sixties. “Through that period I came back to my roots,

one of the reasons for that was because I went to see

Jerry Lee Lewis in Birmingham, and at the time he was

playing only country songs, I came out of that concert

feeling really disappointed, because he didn’t do

“Whole Lotta Shakin´” and “Great Balls Of Fire”,

and it occurred to me that if people come to see me, and

I don’t do “I’m Going Home” and “Good Morning

Little Schoolgirl” then maybe they would feel that way

too”.

The

combination of this thinking and pressure from R.S.O.

records with whom he got a record deal in the States,

led to the new formation of “Ten Years Later”.

Comprising of : Tom Compton on drums, Mick Hawksworth on

bass guitar, and Bernie Clarke on keyboards, they cut

two albums: “Rocket Fuel” 1978 and “Ride On” in

1979. It was the start of a frustrating period for Alvin

Lee, where the output had been dictated more by the

record company demands, then by his own artistic

requirements.

“Ten

Years Later was actually a joke name, it didn’t last

very long. I thought that “Rocket Fuel” was quite

good, and I thought “Ride On” wasn’t. That’s my

personal opinion. There’s not many people that agree

with what I think, even the people who follow it closely.

R.S.O.

specifically

wanted a rock band. They particularly

wanted us to play heavy rock, and so we moved

towards that, but it didn’t happen the way they wanted

it to, and we weren’t

enjoying it that much”.

Since

then, he has released two more solo albums, teamed up

for six months with Mick Taylor with whom he toured in

Europe and

the States, and is currently working on material for a

new album. He’s down to a three piece “Alvin Lee

Band” for touring, comprising of:

Fuzzy

Samuels on bass and Tom Compton on drums, both of whom

are featured on his most recent album release, “RX5. I

talked to him in a sumptuously well appointed flat

located near Holland Park.

Thirteen

years after Woodstock, and approaching his 38th birthday,

his face is lined, and he has put on weight, he remains

courteous and dignified master guitarist.

What’s

your view in 1982 about that Woodstock appearance?

“Actually I saw it only the other day on Channel 4 and

to be quite honest, I was getting really worried before

my bit came up, because I was thinking, “now I’m

going to watch this and I’m going to think, where have

I gone since then?” musically. Often in moments of

doubt, and everyone has moments of doubt, I used to

think, “I’ve done my best gig somewhere in Cleveland

or, I don’t know when it was, but I probably played as

best I’ll ever play”. And I was quite relieved

afterwards, because actually I didn’t play that

well!!! The energy was good, but I did a few horrible

things that I’d never do now. In fact, I’ve improved

quite considerably, so I didn’t feel as bad as I

thought I would.”

Do you think that your best gig’s still ahead

of you? “Hopefully, hopefully”. I always thought

that Ten Years After, had a bit of a problem, getting

that energy across on record sometimes.

“Yeah

– we never cracked that, we never got the energy in

the studio that we got live. To me there’s a whole

different attitude to playing live, as opposed to

playing in the recording studio.

Even

when we’re recording live, I don’t think about the

recording. I play the gig, I play to the people. I show

off a bit, I go for things that I might not get, on the

off chance that I might get them, and often when

you’re that confident you do get them.

“That’s

where the new licks come from, those bravado tries, and

in the studio I kind of go safe. You start constructing

the number and it gets more subtle, and I think what Ten

Years After had live was very unsubtle, and no matter

how we tried in the studio, we just couldn’t get it to

have that rawness. Of course a lot of it is more than

sound at a gig, a lot of it is the environment – the

feedback that you get from the audience. If you do

something a bit outrageous and the audience loves it, it

encourages you to be more outrageous. “There’s no

such encouragement like that happening in the studio.

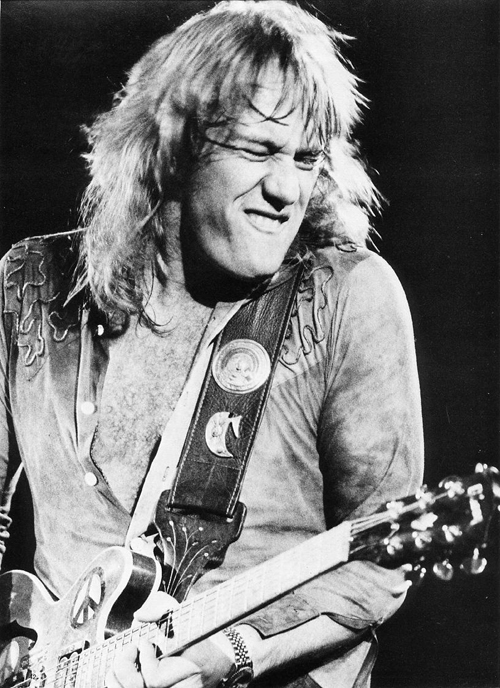

Pic by Barry Plummer

How

much were you influenced by Eric Clapton and Jimi

Hendrix?

“Well

I wasn’t terribly influenced as far as what I actually

played, but what did influence me was the effects of the

way Hendrix played, and the area in which they played,

gave me a good idea as to what I could get away with. I

never tried to play like them, but I could play in that

vein, with no problem.

Jimi

Hendrix to me personally, was an innovator. When I first

heard him I didn’t know where he’s come from; the

closest that I could figure, was like a psychedelic

version of John Lee Hooker. After hearing Hendrix and

getting into him, then I’d suddenly go into an extra

long, sustained distortion bit, and really his music

gave me the idea and the freedom to do that. I’d

probably have not done that before I heard him.

Eric

Clapton:

I

think that I borrowed his vibrato technique; I used to

vibrato very fast, and Eric used to do it so much slower,

and I used to think “now, how can he do a really hot

lick and then go right into that vibrato at the end of

it ? But I liked it. With Eric, it’s easy to see his

roots, you could look into all the Kings – Freddy King

– Albert King and B.B.King and the old bluesers and

things and I knew lot of it anyway.

“I

think you take a bit from everybody you hear. It all

mucks in – into one thing; sometimes I hear a

guitarist that nobody’s ever heard of, then or since,

and you can learn something off of them too. Everybody

who picks up a guitar plays something different, usually

the first thing you do, you just fiddle around, just to

get the feel of the instrument. Those fiddles are often

the basis of their style patterns. Not reading music you

see, I work in patterns and a new pattern, is a good

thing to fall across. I find fewer and fewer the more I

play. They get less and less. There are still hundreds.”

What

advice would you give to an aspiring young guitarist,

who is very anxious to achieve your kind of speed ?

“Well

the speed just came from all that energy. I mean I’m

not really that fast, a guitarist Jazzers play much

faster than me, but they ply smoothly, so it just

doesn’t come across as fast. My so called fast runs

are very staccato and they come out like jarring machine

gun bullets, whereas a jazzer will use a smooth bloopey

sound. I hit every note with attack, and I play with a

lot of aggression: I think it’s more that than speed.

I’ve found the way to practice is when you get new

lines and new licks is to work them really slow and

repeat them over and over again. If you can do three or

four hours a day of that they get faster without you

even realizing it”.

Do

you still use the same Gibson ES-335 with all the

stickers on it ? (Known Affectionately As “Big Red”)

Yeah,

I bought it for 45 pounds actually, in Nottingham, with

case. It was quite a good investment. It’s had a new

neck. I broke the neck at the Marquee. It’s very small

headroom there, and I got carried away with the old

guitar, and chopped the top off. I had to send it away

to Gibson, they kept the old head with the serial number

on it, and spliced a new neck on it. They also

re-sprayed right over the body, and I had all the

stickers on, which is why they’re

still there today. They’re kind of cellulosed

over. It’s a dotted neck. “I’ve got an additional

Fender pick up on which I mainly use in the studio, and

those TP-6 turnable

tailpieces – I like those, they’re great, you

don’t have to take your hand off to tune up. Apart

from that, it’s a pretty regular one. It’s a bit of

a good one.. I think it’s a 1958 model actually.

Now

do you have the action set on it ?

“Pretty

high and hard. The original teacher that

I had did a lot of Django tape stuff, so I got

hard finger pads pretty early. I use a 54 on the bass

end. because I like to hit open E’s a lot and if you

have them much lighter than that, I find they ring sharp

at first, so I have a very heavy bottom and a

comparatively light on the top. For example: From the

bottom up it’s – 54. – 44. – 28.- 15.- 12. and

9.

And

Guitar Pick ?

“I

use three cornered ones. I got about 12 gross of them in

New York one time. With the side scrubbing I wear them

out quite a bit. With the side scrubbing technique, I

can turn it around and get three times the use, a very

hard pick.

What

amplification do you use ?

“I’ve

got a Marshall 50, an old one, a small flashy one and

I’ve got four outputs on it and I use four cabinets.

I’ve always used that, it’s great. I’ve found that

the 100 is just a bit to middley. While the 220’s are

totally useless: One time I had the guys from Marshall

come down, I really wanted to find out exactly why my 50

was so much better than the brand new Marshall 50’s.

– and they said, it shouldn’t be any different, and

they got out the old dentist’s mirror, they looked in

the back, and the guy said, “Oh, this must be an old

one, because they didn’t have these when I’ve been

working here”. He’d found a component. I said,

“Whatever it is, stick it on all of them”, and it

seemed to do the trick actually.

“Also

I power the valves a lot. Hell of a lot of bias on the

valves, so I change the valves once a week on the road;

but that gives you that high sustain. In the studio

I’ve got a 15 watt WEM with one Celestion which sounds

just like a stack of Marshalls milked up, they’re

actually a bit better for

recording”.

What

sort of volume setting do you put that on ?

“Three

quarters to full, I find that the Marshall 50 watts

practically flat out, that’s the best sound. If you

turn it down, it gets a bit dry”.

Do

you have any pedals or use any other effects ?

“No,

I always avoid those. I like a strong lead, that also

gives me the level I need. I sometimes use effects in

the studio, but I don’t put them between the guitar

and the amplifier: I put them after. I do like reading

about all these effects boxes. Makes me laugh; I’m so

glad I don’t have any. How on earth musicians choose

nowadays. You open those books and there’s 80 guitars

and 300 foot pedals to choose from. It was Gibson or

Fender when I started, it was quite easy to choose, if

you could afford it”.

What

Acoustic guitars do you have in your collection ?

"I’ve

got a Martin and a Yamaha, not the most expensive

Yamaha, but it’s got a turn-able bridge so I can use a

wire third if I want. My favourite one is the cheapest

Yamaha in their price range, with gut strings on it.

That’s

the one I pick up and fiddle with all the while”.

Do

you use any unusual tuning at all ?

“No,

very seldom do. I just mess around with them, but I

don’t actually use them. I play bottle-neck in

standard tuning. I’m not a great bottle-neck player”.

What

do you use for a bottle-neck ?

“A

torque wrench thing off of a plug spanner. A very heavy

one. It’s Lowell George’s idea. I got it from him."

Are

you a guitar collector ?

“Semi,

semi. What I do is, if I do a tour of America, I get a

guitar when I get there and use it at the hotel and then

it enters the collection. I’ve got about 40 guitars. I

usually buy novel guitars. I’ve got three favourite

guitars which I keep strung: the rest tend to get stuck

into boxes and end up with rusty strings. I think

you’re well

if you can keep three guitars in good playing

condition”.

It’s

very often overlooked, that as well as being a guitarist,

you’re also a singer.

“Well,

I often overlook it too actually. I don’t really think

about it much, I’m more of a shouter than a singer. I

don’t profess to have much of a voice, but I think

half of it is the effect of singing and playing the

guitar. “With my Chuck Berry upbringing, you phrase

differently, you phrase a vocal lick and then you answer

it with a guitar lick.

I think that’s a quite natural sounding way

of doing it. I also do the odd session, with

people where I put a guitar solo on, and I usually play

all over the vocals, if I’m not singing it. I try to

make the vocals as good as possible, but I’m no Paul

Rogers, and I never will be."

What’s

your view of these bands like “The Who” and “The

Rolling Stones” who are still pressing on after all

these years ?

“Well,

I think it’s nice for us, the listeners as it were:

there was a lot of pressure for me to keep Ten Years

After together from the business side of things, but I

knew that it wouldn’t work.. I could feel from the

other guys, that there was no pulling in one direction,

and the managers wanted me to, if I wanted to change,

they wanted me to keep the Ten Years After name.

Business wise, and looking back, that would have been

good for me to do for the money, but not for the others

in the band. For me it just didn’t seem right. Ten

Years After was the four of us, and if I was going to

change the musicians, I’d call it something else."

How

democratic or otherwise was Ten Years After ?

“It

was very democratic. It was an equal band all the way

down the line, and with any democratic band like that,

because I was the lead guitar, and singer, I got more

spotlight, I got to do more interviews which I really

didn’t want to do actually. I was keen to spread the

load, but with that also came a little bit of bad taste

from the other boys in the band, which caused a little

bit of friction”.

You

also wrote and handled most of the production !

“Yeah,

right, and people used to say to me – You’re Ten

Years After; and I’d say, “I’m not”. I didn’t

really want to be. I didn’t want to take all the blame

to be honest”.

What

are the other guys doing now ?

“Leo

Lyons is producing, he’s got a studio in Oxfordshire,

and he’s doing pretty good. Good producer actually. He

did some time at Wessex studios; he knows his onions

(Business). I’m still in touch with Leo, I go down and

play him my tunes and things. Ric Lee was playing in

Stan Webb’s Chicken Shack, but he’s doing managing

now; I think that’s taken over from his playing more.

Chick Churchill, is not in the music business anymore

unfortunately. I don’t know if that’s terminal or

not. He’s got into music publishing a bit”.

Can

we talk a bit about your recent activities; since Ten

Years Later you’ve been working solo.

“Ever

since 1979-1980 I’ve found myself up until last

Christmas being pressured into making albums all the

while, when I haven’t really got enough fresh ideas

and that’s a trap. As much as I’d like to think of

myself as a musician above being a rock star or whatever

you’d like to call it, when people are waving money in

front of your nose and they want an album, you tend to

get it done whether you think you’re ready or not.

“I’ve been doing that and the last two albums I did.

I didn’t even have enough songs to dare start. I got

three songs for the last album – called RX5, and I

only thought two of them were any good anyway, so it’s

just a matter of getting enough tracks down to make an

album”. Isn’t that a rather cynical way of doing it

?

“Oh

it’s terrible.

It’s

just the way things were, where I was at the time and

everything else, but I have stopped it now. I realize if

I’m going to keep on making albums that I can’t

even------I mean people used to ask me about RX5 – and

I used to say, “I hate it, all of it. It’s

ridiculous you know, because people who buy albums or

even get them free, when they hear that, to them

that’s everything I stand for and do at the time, and

it’s too important just to go bumming them out.

So

for the next nine months I’ve been writing pretty

solid. I’ve got a target not a deadline to start

recording in February. But I’m certainly not going to

release anything or let anything out until I’m really

happy with it. I can’t hope for an album to be

successful if I don’t like it, and if it was it would

be silly, because I’d have to make another one like it

then.

“So,

I’ve been delving back into my roots and writing new

stuff, old stuff…..and just a lot of writing. Playing

more for my own pleasure, more than I’ve done in

awhile”.

Alvin,

I noticed at a previous meeting, where liberal supplies

of alcohol were available, that you were very careful

not to drink….any reason for this ?

“I

never used to drink, and then I did start for awhile,

and like most things, I went over the top for awhile,

and then I just cut it out altogether. It didn’t

really suit me, being an old hippie. I’ve never been a

serious drinker, but I did start getting into playing

poker with a bottle of scotch, that was with Steve Gould

and Mickey Feat actually, not putting them down,

they’re wonderful guys. I didn’t have to join in”.

“I’ve

put on a lot of weight as well, and it was just

generally no good for my health. I had a good clean

out….I was going down the old Elvis road at one time,

getting very puffy and doing lots of other things that I

shouldn’t have been doing. But fortunately, I saw the

light, and I saw myself before it was too late”.

Do

you have a recording contract at the present time Alvin

?

“No,

as a matter of fact I don’t at the moment. I’m

looking for a new one right at this very moment, but I

do have an option with Atlantic in the States, they’ve

got first choice as it were”.

Are

you going to do any gigs in Britain ?

“I

haven’t done any for a long while. I don’t do much

in England. Ten Years After never did that much in

England, and the last time I tried it, there was very

poor attendance anyway. So that has kind of put me off

trying, although I’d love to. I wouldn’t mind

playing the Marquee again actually, just to see if

it’s anything like it used to be. “I’ve played the

Odeon. Hammersmith a couple of times, a token English

gig, but there seems more interest abroad.

Possibly

because when Ten Years After were kind of hitting it, I

preferred not to. Well the whole band preferred to kind

of keep a low profile in England, because we lived there,

you know what I mean ? It’s great going over and being

a rock star in America, but when you get home it’s

also as nice to be able to walk the streets without

having any problems. The main reason really why I’ve

always been a musician

is that I can’t do anything else. I don’t

have a proper trade you see”.

It’s

certainly been a reasonable trade so far hasn’t it

Alvin ?

“Yes,

but my attitude has always been that a musician’s only

security is that you can sing for your supper. If you

can make ten pounds down at the local pub, then you can

eat. That’s really all you can count on, you can’t

count on thousands of pounds and being successful. A lot

of that’s fashion, waves of fashion. You can catch a

wave and then lose a wave, and then you have to go back

and catch another one.

The

working for your supper theory keeps you more level

headed. I’m certainly not afraid to get up at the

“Red Lion” and do a bit – quite enjoyable

sometimes, things like that. You lose the tension; put

your beer on the amplifier, and turn your back to the

audience occasionally – it does a musician a world of

good to not have to take his profession so seriously.

“But

there again, even when I get up and jam, I like to

deliver something; I wouldn’t like to get up and jam

on a bad guitar, that I can’t play because I

……….somebody’s going to remember it. You’ve

got to deliver something – and make people think about

it when they go home”.

|