|

|

|

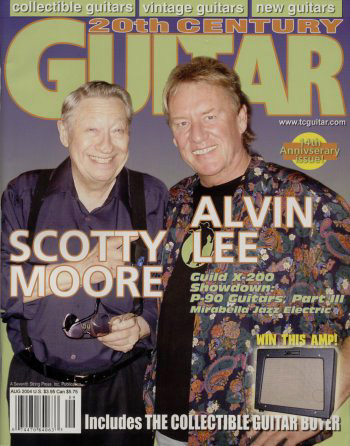

That's All Right 50 years of Rock ‘n’ Roll

with Alvin Lee

and Scotty Moore

Interview by Robert

Silverstein

|

It was fifty years ago-on July 4, 1954 in Memphis, Tennessee

to be exact-that guitarist Scotty Moore met a budding singer

named Elvis Presley. The very next day, on July 5th 1954,

Scotty and Elvis-with Bill Black on bass and Sun Records

founder Sam Phillips in attendance-recorded “That’s All

Right” and the rest is rock ‘n’ roll history. |

|

Celebrating 50 years since the first Sun Sessions and the

birth of rock ‘n’ roll, RCA Records has released Elvis At

Sun-a nineteen track 2004 CD containing some of the great

tracks Elvis made with Scotty Moore and Bill Black at Sun

including “That’s All Right”. Coinciding with Elvis At

Sun, RCA has also released Memphis Celebrates 50 Years Of Rock

‘N’ Roll, a 21 track CD combining a range of early Sun

classics from Elvis, Scotty & Bill, Carl Perkins, Johnny

Cash, Roy Orbison, Jerry Lee Lewis.

Flash forward 50 years,

from 1954 to 2004, and the release of a new recording

celebrating the glory days of ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll.

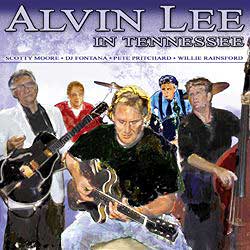

Released on Rainman Records, Alvin Lee In Tennessee features

British blues-rock guitar icon Alvin Lee joined in a musical

reunion with original Elvis band members Scotty Moore  and

drummer D.J. Fontana. Showcasing Alvin’s songs and vocals—with

key contributions from Scotty and D.J.—Alvin Lee In

Tennessee merges the finest elements of ‘50s rockabilly with

the blues-rock power Lee successfully brought to bear with his

‘60s band Ten Years After. Honoring the 50th anniversary of

rock ‘n’ roll and the 2004 release of Alvin Lee In

Tennessee, 20th Century Guitar and mwe3.com music editor

Robert Silverstein spoke to both Scotty Moore and Alvin Lee in

early June 2004 on a range of topics. Scotty spoke about

recording with Elvis at Sun Records, Alvin’s CD and the 2004

DVD reissue of the Elvis ‘68 Comeback Special. One of the

original architects of ‘60s British blues-rock, Alvin Lee

was eager to point out how influential Scotty and D.J. Fontana

were during the making of Alvin Lee In Tennessee while also

sharing musical memories of Ten Years After, the ‘69

Woodstock festival and much more. and

drummer D.J. Fontana. Showcasing Alvin’s songs and vocals—with

key contributions from Scotty and D.J.—Alvin Lee In

Tennessee merges the finest elements of ‘50s rockabilly with

the blues-rock power Lee successfully brought to bear with his

‘60s band Ten Years After. Honoring the 50th anniversary of

rock ‘n’ roll and the 2004 release of Alvin Lee In

Tennessee, 20th Century Guitar and mwe3.com music editor

Robert Silverstein spoke to both Scotty Moore and Alvin Lee in

early June 2004 on a range of topics. Scotty spoke about

recording with Elvis at Sun Records, Alvin’s CD and the 2004

DVD reissue of the Elvis ‘68 Comeback Special. One of the

original architects of ‘60s British blues-rock, Alvin Lee

was eager to point out how influential Scotty and D.J. Fontana

were during the making of Alvin Lee In Tennessee while also

sharing musical memories of Ten Years After, the ‘69

Woodstock festival and much more.

RS: Hi Alvin, how are you doing?

AL: I’m doing fine, thank you!

RS: You’re living in Spain?

AL: That’s right.

RS: Do you still spend time back

in England anymore?

AL: Oh yeah, I just did a huge tour in England. Well, huge

for me anyway. (laughter)

RS: Spain has a rich guitar

tradition.

AL: I know, the flamenco guitar is fantastic.

RS: I heard you were supposed to

come over to the States for some shows this June but they got

canceled because of work visa problems?

AL: Yeah that’s right. I went to the American embassy for

me work visa and it didn’t pan out. My name wasn’t on the

list. It’s getting tough these days.

RS: I spoke to Arnie Goodman and

he said it’s a sign of the times.

AL: Oh, yeah. I like Arnie. How’s he doin’? I haven’t

spoke to Arnie Goodman for years!

RS: He’s Mr. Blues Expert.

AL: Well, he always has been, yeah. (laughter)

RS: He’s a nice guy...

AL: He’s great, yeah...

RS: You’re going on to tour in

Italy and Sweden next summer?

AL: That’s right, yeah. I did this seven week tour of the

United Kingdom with Edgar Winter and Tony McPhee, which was

great. I haven’t done it in while and it’s actually got me

back into playing regularly again which is great.

RS: You finished the UK tour with

Edgar Winter on May 27 at the Royal Albert Hall? That’s an

amazing place...must have been a great show.

AL: That was a great night actually. It was a great end to

the tour. We had a good time. We had a good party afterwards

too! (laughter)

RS: Starting off asking some

questions about the 2004 release of Alvin Lee In Tennessee,

can you reflect back to when you were 14 and you joined the

Elvis Presley fan club in order to get pictures of Scotty

Moore and his guitars.

AL: That’s right, yeah. I don’t know what it was. I was

just starting to pick up the guitar and fool around with it

and I’d taken a few chords lessons. I’d been brought up on

blues. My father was an avid blues collector and he had a 78

collection of some very ethnic chain gang songs and Big Bill

Broonzy and the like so I was brought up on that music. I

started off playing a clarinet when I was 12. And I heard

Charlie Christian playing with Benny Goodman and thought, ‘that’s

more what I’d like to do’, so I swapped the clarinet for a

guitar. And till I heard Chuck Berry I was kind of pretty much

into jazz chords and things. I used to listen to Barney Kessel

and Django Reinhardt and early George Benson. But I first

heard Chuck Berry and I thought, ‘this is the blues all

rolled into rock and roll as well.’ I loved the way Chuck

Berry played two notes at a time when he solos. And of course,

the other great guitarist was Scotty Moore. The “Heartbreak

Hotel” solo was the first one I ever heard. And the second

“Hound Dog” solo, which is a classic till this day. And

just his talent and his style and the way he made things work.

And I was just inspired by that. I never actually copied these

guys. I used to copy their style but not their notes. You know

what I mean? So I would play in their style...it’s what

kicked me off. D.J. Fontana too...who I think, still is one of

the greatest drummers in the world.

RS: Can you recall the first time

you met Scotty Moore and how that evolved into the making of

Alvin Lee In Tennessee?

AL: I first met Scott, I was in Nashville as a fan in 1995.

And somebody took me round to meet him. I got my photograph

taken with him and got his autograph. All the fan stuff, y’know?

Asked him all the fan questions and we kind of struck up there

but it wasn’t until four years later, 1999 it was that

Scotty was launching his guitar for Gibson, the Scotty Moore

model. And it was a jam on stage at the AIR studios in London.

They invited me down and I got up and did a medley of Elvis

songs with Scotty and D.J. I just loved it. I mean it was

great. It was magic and I thought, ‘I’ve got to take this

further.’ So I asked Scotty, ‘Any chance getting you guys

in the studio sometime?’, and he said ‘sure thing.’ So

the idea was born there and then.

RS: It’s interesting that some

of those early Elvis sides like “That’s All Right” didn’t

even have drums on it!

AL: No drums. The very early first sessions had no drums at

all, yeah.

RS: What was it about Scotty Moore’s

early rock and roll guitar style with Elvis that intrigued you

most?

AL: It was a mixture of...he played melodies for solos

rather than kind of noodling. I play from the hip generally. I

play kind of stuff all over the place. But I’ve always

admired guitarists, people like George Harrison too, they can

construct a solo which is singable. But Scotty would do that

too whilst exploring interesting runs and he had a little bit

of jazz stuff going there, which is quite unique really.

RS: What did you think of Elvis as

a guitarist?

AL: Didn’t think of him as a guitar player. A damn good

singer. (laughter) One thing I thought when I went to play

with Scotty at that jam, I said, ‘well look, I don’t want

to be up there as Elvis for the night, y’know? ‘Cause that’s

a tough act to follow and I can’t fill his blue suede shoes.’

He said, ‘oh, no...just get up and have a bit of fun.’ And

that was basically what it was about. But for the recording, I

wanted to record original songs. I went over to Nashville. I

had, I think twenty seven songs and I even had a stash of

about fifteen songs...all Elvis like “Shake, Rattle &

Roll”, in case my songs didn’t work. But fortunately I

didn’t have to use those. I went over to record for three

weeks and in two days we got down eleven tracks. So, I had a

lot of time to spare. Those guys are very good and know what

they’re doing in the studio. They go for the feel and the

groove in the pocket. It was beautiful.

RS: You’ve called D.J. Fontana

the best drummer in the world. How cool is that to have two

key Elvis band members backing you up on the Alvin Lee In

Tennessee album?

AL: (laughter) I know. It was great. I was still like a fan

when I got there. You know what I mean? In Scotty’s studio,

he’s got pictures of him with Elvis, trophies and gold

guitars...stuff all around. I mean, like a school boys dream.

It took me back to being a school boy. I felt like a young kid,

but they made me feel like one of the boys, which is a great

compliment. They could have kind of treated me like an upstart

but they made feel really at home and like one of the boys,

which was great.

RS: Interestingly, you’ve said

about making the Alvin Lee In Tennessee that ‘it was time to

put the roll back in rock and roll’.

AL: That’s right! It’s been missing for a long time.

The English style of rock music came from rock ‘n’ roll

but it was always kind of done with kind of more aggression

and more adrenaline.  And of course the English rock music

turned into the stadium rock, which became louder and even

turned into heavy metal. So the ‘roll’ in rock ‘n’

roll, which D.J. Fontana is the master of, kind of got lost

somewhere. And I thought it was possibly the best bit, ‘cause

it’s the swing, it’s the groove, it’s the finesse. And

when you hear those old Elvis records, which you think are

really loud and raucous...they’re not so loud and raucous.

In fact, they’re steady. They’ve just got that swing

groove which makes them rock...and roll. And of course the English rock music

turned into the stadium rock, which became louder and even

turned into heavy metal. So the ‘roll’ in rock ‘n’

roll, which D.J. Fontana is the master of, kind of got lost

somewhere. And I thought it was possibly the best bit, ‘cause

it’s the swing, it’s the groove, it’s the finesse. And

when you hear those old Elvis records, which you think are

really loud and raucous...they’re not so loud and raucous.

In fact, they’re steady. They’ve just got that swing

groove which makes them rock...and roll.

RS: Scotty only played guitar on a

couple tracks, but you’ve said he kind of masterminded the

sessions.

AL: Oh yeah. Well he put the band together to start with. He

got Willie Rainsford on the keyboards. I didn’t know Willie

before then and he was perfect for the job. And the bass

player, he brought in Pete Pritchard. He’s actually from

London. And I just used him on my last tour. He’s great. He

plays double bass and he plays electric bass as well. And

Scotty brought him in from England so I figured he must be

good, ‘cause (laughter) there’s a hundred bass players in

Nashville! But this guy, he’s kind of brought up on Bill

Black. And he know all Bill Black licks and he can slap the

bass just like that. He’s great too. He’s a great

character. We put about four tracks down in the studio and

Pete turned to D.J. and said, ‘hey D.J., you’re pretty

good at this, have you ever thought of taking it up for a

living!’ (laughter)

RS: Pete at one time played with

Chuck Berry and even Bill Haley.

AL: That’s right. He’s an English stand up bass player

and he knows every American rock and roll star who’s come

over here. He used to get the gig.

RS: You’ve said that nothing

comes close to your ‘Big Red’ Gibson 335. Did you mostly

use the 335 on the Alvin Lee In Tennessee CD?

AL: No, I didn’t use that one. Actually (laughter), I

borrowed a guitar in Nashville. (laughter) I figured taking a

guitar to Nashville is like taking, what we say, coals to

Newcastle. I suppose you’d say, taking sand to the desert.

Also, I got fed up with carrying guitars on airplanes these

days. It’s great if you can pick up a guitar and play it. I

mean, it’s a bit risky really. When I do my touring and

stuff I take my own guitar but it’s great when you can pick

up one. And in Nashville, the guy at Valley Arts Guitars...he’s

got about six hundred Gibsons and just said, ‘help yourself’.

RS: So which guitars did you use

on the album?

AL: It was a 335 type of guitar. It was a sunburst version.

It was a prototype of a different pick-up situation, but it

was pretty much a 335. I’m playing it on the album cover,

you can see it so...the brown version.

RS: So you still have your

original 335?

AL: Yeah, unfortunately that’s got so valuable, I can’t

play it anymore, which is very sad. I mean the last thing I

ever wanted was to have a guitar stuck in a vault somewhere.

Some guy offered half a million dollars for it last year,

which kind of makes me want to not take it on an airplane and

not leave it in the back of a van. You know what I mean? I

turned it down because I wrote this song once called, “There

Once Was A Time”...an old Ten Year After song (with) ‘I’d

never sell my guitar because that would be a sin’. It’s

not the money, I mean it’s a great guitar. The sad thing is,

I’m not playing it. I just don’t take it on the road. If

it got broken or stolen I’d be...devastated.

RS: Are there any other vintage

electrics or archtops you’re using on the CD?

AL: I always use a 335 when I’m getting serious. I’ve

got a nice Strat that I fool around with. I’ve got a

Steinberger which I use for sessions. I’m jamming alot. We

have these jam afternoons over in Morbello. Boz Burrell lives

out here, Bad Company bass player. And Trevor Marais, he’s

got a studio here, which is where I actually mixed the album.

He used to play with a band called The Peddlers in England and

he went on to run professional studios all his life. He’s a

drummer, he’s a great drummer so we have these jam sessions

over there. In fact, I take this Steinberger and I take this

tiny little box, called Pandora’s Box and plug it straight

into the desk and it’s great, it’s great for jams. It’s

a toy but it’s great. You can get damn close to...it’s

like having about fifty amplifiers with you. So I enjoy

mucking around with that. I’m doing another project with

Trevor ‘cause I think I can see Africa from where I am here.

So we go over to Africa and we’re recording with a load of

African drums. So it’s going to be like heavy rock guitar,

full distorted rock guitar with stacks of Marshalls and stacks

of African drummers. It’s going to be a jungle-rock fusion.

(laughter) It sounded very good. We’ve done a few runs, a

few tests on it. It sounded great. ‘Cause it lets me get

back to my mad guitar style. ‘Cause the style I play with

Scotty on the In Tennessee, I’m kinda playing...when you

play with D.J. Fontana and Scotty Moore, you play tidy, you

know what I mean? And of course with the jungle drum project,

then I just go mad. Just attack the guitar with fervor. I

think I need to do that. That’s the next thing I want to do.

(laughter)

RS: So that style you’re playing

with Scotty you call ‘keeping it in the pocket’... can you

expound on the definition of that musicians term? RS: So that style you’re playing

with Scotty you call ‘keeping it in the pocket’... can you

expound on the definition of that musicians term?

AL: That’s right and I’ve adopted it for this album. I’m

not going to follow that style from here on in. That’s what

I’ve pretty much always done on most of the albums that I’ve

recorded. I play in the kind of the style of the year as it

were. My own style is between blues and rock. Early on, I

suppose I was a blues player with heavy metal leanings. I’ve

always been trying to push the boundaries a bit and kind of

get out of being ordinary and average. Not that there’s

anything wrong with that. B.B. King is good enough or Freddie

King is good enough, so who needs two of them. I figure I

should do something which comes from within me.

RS: Early Ten Years After albums

like SHHH! and Cricklewood Green were ahead of their time.

AL: I thought so too! (laughter) They were great days. It

was the time for breaking barriers in those days. I mean, if

you made an album without breaking a few barriers then it was

passe, wasn’t it? I’ve got this anthology album out, it’s

called Alvin Lee Anthology and I did this interview which the

guy used for the liner notes. I don’t know if you heard that

one ‘cause it’s a good mixture of all the stuff I’ve

done over thirty years. It might only be out in Europe at the

moment. I think it’s due to be released in America this year,

come to think of it. In the interview I said, ‘those were

the days when we thought we were changing the world’, and I

went on to say, and I’d forgotten I said this and when I

read it I cracked up. I went on to say, ‘in fact we did

change the world back in those days, the only thing is, it

changed back again while no one was looking.’ And it’s

kinda true, y’know? It’s like...all that, the underground,

which was so great, I loved being part of the underground. We

used to play Electric Factory and The Boston Tea Party and The

Fillmores. Those kind of gigs with light shows and kind of

very stoned audiences. And it was called music for heads in

those days and it was called underground. And the early days

of underground you know you’d do a show with a rock band, a

poet and a string quartet or something. And it was really kind

of arty. That was a great involvement. It was very bohemian

and I really enjoyed being part of that. And that kind of

evolved into what later became the peace generation I suppose.

RS: Before the ‘70s malaise?

Sort of before punk and soon after MTV.

AL: It all kind of went inwards rather, didn’t it? That

was the thing.

RS: But some of the music you were

making with Ten Years After back then...I call it baroque

blues or something.

AL: That’s an interesting description, yeah.

RS: The lead off track on the In

Tennessee album, “Let’s Boogie” kicks off the CD in

style with it’s Berry meets Elvis bounce. It sort of sets a

solid tone for the album.

AL: Yeah, I like that one, yeah. That was the obvious

direction because, I mean to me, that jump-jive stuff is where

rock ‘n’ roll comes from. And I think that’s what D.J.

and Scotty were listening to when they were learning. This is

what’s great about music, ‘cause every time you find an

innovator of music, you find out what he was listening to. And

rock ‘n’ roll goes back to the early 40’s, or even

earlier but if you go to the jump-jive bands in Harlem in the

‘40s? They’re playing rock ‘n’ roll. With a lot of

swing.

RS: The song “Tell Me Why” has

a cool kind of Ten Years After feel.

AL: It does have a little bit, doesn’t it? It’s

interesting you should notice that.

RS: Scotty played on only a couple

of songs....

AL: He only played on the two...he had this ear problem. He

actually went totally deaf in one ear, which was quite

devastating and he was very worried if he was going to mess

things up so he sat out on the others. But his input was

phenomenal though. I mean, just him being there...he’s a

lovely man, a wonderful guy. He’s been there and done

everything I can think of.

RS: Another highlight on the new

album featuring Scotty, “Let’s Get It On” was

reminiscent of the spirit of some of your work with George

Harrison. Is that a valid comparison?

AL: I wouldn’t have actually thought of that myself.

George didn’t do much boogie-woogie stuff. He was more of a

chord man and a melodic man. When you get that anthology album,

there’s “The Bluest Blues” on there, which is one of

George’s best guitar solos ever. He plays this slide guitar

solo, which just sends shivers down your spine. And he’s

great for that. He’s just got the feel and the touch and the

sensitivity. And he keeps me in line too, ‘cause if I start

to overplay, and then George comes in and he plays in such

sweet, pure tones. And he brings me back down again to being

melodic. That’s one of my favorite tracks of all time, “The

Bluest Blues”.

RS: Can you remember the first

time you met George?

AL: I met him through Mylon LeFevre. Mylon came over to

record my first solo album in ‘72, which was On The Road To

Freedom. Mylon came over, in fact Mylon came on a Ten Years

After tour. We used to hang out together and write songs after

the gigs and things and became kind of rock and roll buddies

on the road. Then he came over to England and we wrote some

more. And then I built my first studio, Space Studios, in

England and Mylon said, ‘I’m going to go out and get us a

band now!’, ‘cause the studio was finished. He said, ‘where

do all the musicians hang out?’ And I said, ‘at the

Speakeasy in London I think.’ And Mylon went off. (laughter)

And he came back about four hours later with George Harrison,

Stevie Winwood, Jim Capaldi, Ronnie Wood...(laughter) He said,

‘man, I’ve got us a band!’ (laughter)

RS: Not a bad start!

AL: No, it was pretty good, yeah. Mylon was good at that.

He was hustling everbody. He said, ‘man, I just love your

music.’ He hustled George into... George had this

song...Mylon said, ‘any of your songs we could do George, on

this album?’ And George said, ‘there’s a lot of good

songs on the albums, why don’t you do one of those?’ Mylon

said, ‘George, you do them so good, I would never try and

follow you. We need a song you haven’t recorded yet.’ (laughter)

So George said, ‘there’s this song called “So Sad”,

which I’ve been working on and I think it could be a hit

actually.’ Mylon said, ‘I’ll take it!’ (laughter) It

was all down to Mylon actually. He kind of got me in touch

with George originally. Having a guy from Atlanta, Georgia in

the Oxfordshire countryside was quite a trip. You take him

round anywhere and as soon as he started talking, people just

fell in love with his accent.

RS: You recorded a remake of the

Lennon-composed Beatles song “I Want You” (She’s So

Heavy)

AL: That’s right.

RS: And George played on it. How

cool is that?

AL: That was very cool. Yeah. He played slide on that. And

he told me, I didn’t realize it, he played that with his

fingers when he started on the original Beatles version by

bending the notes, which sounds like a slide guitar. That was

great yeah. That one and “Yer Blues” I think are two of

the Beatles tracks which really rock.

RS: “Yer Blues” almost sounds

like it could be a Ten Years After song.

AL: Yeah, it’s kind of more my style. That’s the kind

of Beatles that I like. Strange enough, when The Beatles came

out I wasn’t a big fan, I’ll tell you why. ‘Cause I was

going around doing Eddie Cochran and Chuck Berry songs in the

early ‘60s and then when The Beatles came out people said,

‘oh, I like that “Roll Over Beethoven, that Beatles song

you did.’ (laughter) I just said, ‘that’s not a Beatles

song!’ I suppose to my mind in the early days, The Beatles

were considered a bit of a hype-y pop band, suits and haircuts

and everything else. I was more into the blues and being a

musician.

RS: The Beatles turned me on to

Chuck Berry who was a few years before my time.

AL: That’s right. First time I went to America...I told

you my father brought me up on Muddy Waters and Big Bill

Broonzy, so when I first went to America I assumed that

everybody in America would be aware of Muddy Waters and Big

Bill Broonzy and I was amazed to find they weren’t. It was

like their own musical heritage. They were into Jefferson

Airplane and Woody Guthrie but the blues seemed to get left

behind somewhere. So in fact, The Beatles did do a big favor,

and The Rolling Stones for that matter of bringing awareness

back to those guys.

RS: Especially in the early days.

It was great hearing George singing “Roll Over Beethoven”

AL: (laughter) He had his own little version of that, didn’t

he?

RS: It’s the 35th anniversary

this summer of Woodstock.

AL: Is it? f

RS: 35 years ago, the Summer of

‘69 was a huge turning point for you and Ten Years After.

The band released Shhh!, which next to Cricklewood Green is my

favorite TYA album. In 1969 TYA played Woodstock. How’s your

memory of the ‘69 Woodstock festival?

AL: It’s pretty....I’ve pieced it back together! (laughter)

It was a very special event but at the time nobody really was

sure about that. The first realization of it being anything

other than another date on the list was when we were told we

couldn’t drive into the festival site ‘cause the roads

were all blocked and it had been declared a national disaster

on the radio and we had to take a helicopter in. And to me, I

thought ‘well, this is going to be interesting.’ (laughter)

And it certainly was. Flying over the audience, a very strong

smell of marijuana wafting through the roter-blades, was a

good way to start the day! And had it been running to plan,

which is wasn’t, we’d have probably just flown in and

played and gone again and been none the wiser but as it

happened we got there and had to wait a long time and then the

rain came down just as we were about to play. So, nobody could

go on stage ‘cause there were electric sparks jumping around

and they wouldn’t let anyone play so I said, ‘C’mon, let’s

play! If we get struck by lightning, think how many records we’ll

sell.’ At that age, who cared? (laughter) We couldn’t play

so I went out into the audience. I went out for a walk around

the whole site. Went round the lake and I kind of joined in

with the audience as it were. Nobody knew I was anybody in

particular. I looked like just another freak. They were

inviting me to have food with them and smoke drugs with them

and everything. Anything that was going, was shared. It was a

great vibe. So I got into the actual other side of it. ‘Cause

backstage, although it was supposed to be three days of peace

and love, there was quite a bit of jostling and managers there

saying, ‘I want my band on next’, all this stuff. And in

fact, when I came back, (laughter) from my trek, Country Joe

had set up his gear and had rushed on stage before me, so that

they didn’t have to go after Ten Years After, which was kind

of funny. So it was even a longer delay. I actually went out

into the audience to get some cigarettes. Backstage had run

out of cigarettes. So I thought, ‘I’ll go and blag some.’

I walked around there for two hours, came back with about

sixteen joints but no cigarettes. In fact, they had to drop

cigarettes in by helicopter. The only thing to smoke was grass.

(laughter) It was funny, dropping food, blankets and

cigarettes.

RS: Ten Years After played

Woodstock on that final Sunday with Hendrix, The Band and CSNY

on the bill too...

AL: I didn’t say that, and I’m not sure what day we

played. What day it was, I couldn’t tell you. It’s in a

book somewhere. (laughter)

RS: Did you get to see Hendrix

play there?

AL: No, he didn’t play till like six in the morning. So

had it been the same day, it would have been twelve hours

later. I got to see Country Joe...who else did I get to see? I

can’t remember. There was a lot of purple haze there.

Difficult to see through the purple haze. But I do remember my

walk out. I don’t remember much about playing but I

obviously had a good time. (laughter)

RS: It’s interesting to note

that the same summer of ‘69, before Woodstock, TYA became

one of the first rock bands to ever play the Newport Jazz

Festival.

AL: Yeah, that’s right. I think were the first band to

play rock music at the jazz festival. I met Miles Davis there.

He was a weirdo. I liked him.

RS: That confirms my belief that

Ten Years After were one of the first bands to combine jazz

influences.

AL: I think so...the Undead album was very jazzy all the

way through actually and that was the first live album of Ten

Years After. And when I’d recorded that I thought, ‘well

what on earth can we do now?’ ‘cause that’s what the

band does, that’s what it’s good at. That says it all. So

that’s why I decided to go into the kind of experimental

mode of Cricklewood Green. Well, Stonehenge I think was the

next one which was quiet psychedelic and experimental and

possibly drug influenced. (laughter) It was all cool then,

wasn’t it?... wait...I’ve been given a piece of paper here.

We played Woodstock on Sunday, the 17th of August.

RS: Newport and Woodstock, how

would you compare the two?

AL: There were tons of festivals around that year. I

remember I did the Texas Pop Festival, the Atlanta Peace

Festival...and to be honest, I thought they were actually

better than Woodstock as far as an organized gig went. I mean

Woodstock...having played Woodstock and moved on...the

helicopter flight and the fact that it was the largest number

of people was kind of cool but to be honest, you don’t

notice, you don’t count the people when you’re there. Any

crowd over fifty thousand is big. If it’s a hundred thousand,

two hundred, three hundred...you don’t really see that much

difference. It’s just that the sea of heads goes back a bit

further. You know what I mean? When you’re on stage, you

tend to relate to the people who you can see around you. At

least the faces. And the rest is like a mass that goes off in

the distance. So, it wasn’t that different. It was very

unorganized. It didn’t feel that big. And when we went on to

play, we carried on playing the same kind of underground gigs

for a year. It wasn’t until the movie came out that it made

all the difference. And the movie was the kind of hype and

that’s what caught people’s attention and band crossed

over to the other lot. (laughter) Woodstock/Newport I was keen

to be kind of the rebel. There’s enough jazz there already.

It’s funny, I’ve always found this about jazz

festivals...if you go on late in the evening, when they’ve

been listening to jazz all day. Boy, are the ready for some

blues and rock ‘n’ roll. ‘Cause sometimes the jazz gets

a bit too much. Jazz is good, jazz is interesting but often,

it doesn’t have that flow. The flow of a good blues, so I

think that audiences have been listening to jazz for three or

four hours are wide open for some blues and rock. So, that’s

what I did. Still works today.

RS: In 1988 you recorded a track

called “No Limit” for the Guitar Speak label headed up by

Miles Copeland.

AL: Oh, that’s right, yeah. It was my first trip into

kind of electric drums and computerized rhythm sections. That

was the forerunner of what was going to be an instrumental

album. It just never came together because I ended up in the

studio working with computers and to be honest after about

three months of that I kind of disappeared up my own rear end!

(laughter) It was fun but to me, it’s not like playing live

with a rhythm section. It’s kind of interesting. I did

similar stuff with the synth player from The Art Of Noise, J

J. Jeczalik. That was around the same time, doing lots of

instrumentals. It’s sitting around in the vaults of Space

Studios actually, I just never got around to finishing it.

RS: Does the new Alvin Lee

Anthology feature Ten Years After stuff?

AL: No, no it’s all my own personal stuff away from Ten

Years After.

RS: Any other huge guitar or jazz

influences?

AL: I could mention George Benson, Barney Kessel, Wes

Montgomery and of course, Django Reinhardt ‘cause I

originally learned to play rhythm, Django Reinhardt style.

That was when I was thirteen years old. ‘Cause that’s what

I love. I even used to think of my original band, the Jaybirds,

which was the forerunner of Ten Years After. And we used to do

like swing, Count Basie swing stuff and stuff like that for a

three piece band. And that was very intricate but it actually

works but alot of it is that vamping guitar which George

Benson does so well, and Charlie Christian. It’s a little

art to itself and it kind of disappeared after 1958. Vamping

disappeared. Alot of guitarists today, and there’s some

great, young guitarists around but they don’t put the time

in on the chords and the rhythm. And I think rhythm is very,

very important. I mean I enjoy playing rhythm guitar, or like

chop rhythms, as much as playing lead guitar. That’s where

it all comes from and you’ve got to hear that before you can

hear what notes you want to put in. Once you’ve got the

dynamics of those rhythms, then your solo work just takes off

in a world of it’s own. And I think the rhythm is very

important. I see alot of guitarists today, they play Eddie Van

Halen lick and then I say play the chord of F! (laughter) and

they sometimes struggle. Alot of motivation these days is to

become a rock star, which I’ve always found a bit sad

because...I was looking at some adverts in one of the guitar

mags and it said, ‘well, you’ve got the looks and you’ve

got the right guitar and the right clothes and now you need

the right sound’, which is totally wrong, I mean you need

the sound first. (laughter) That’s the way to go. I think

the motivation to be a musician is much wiser because it lasts

much longer. I’ve been a professional musician now for, must

be thirty five years now. And rock stars might last two or

three or four years and if you’re a serious musician you can

make a career of it. And it’s more rewarding. Actually the

stuff I’m going on to play now to me, this thing with Scotty,

the African drums...it’s much more rewarding musically. I’m

actually getting control of what I’m doing these days. I’m

actually really enjoying what I’m doing and enjoying trying

these projects and I have to make it a special project to keep

me interested. Obviously after how many albums...I don’t

know, twenty five albums? You get a bit jaded. I’m not going

to go into the studio and record another straight rock and

roll album. It’s got to have an angle for me. It’s got to

have an interest. It’s got to be a project which has

interest. And that’s what Scotty and D.J. did for me. ‘Cause

they took me right back to my roots and made what was

originally exciting to me to listen to, exciting to me to

play. And it’s a kind of a full circle. And I feel very

honored and I thank Scotty and D.J. for doing that.

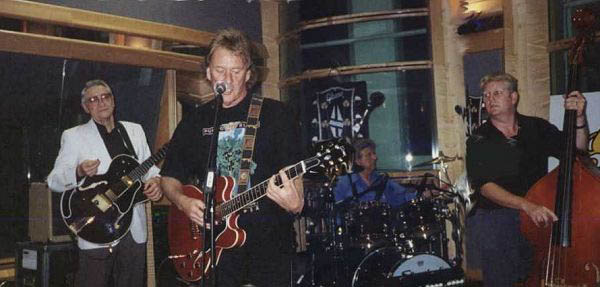

Photo by Pete

Pritchard

RS: Too bad you didn’t film the

In Tennessee sessions.

AL: Not officially, no. Maybe a home movie of it, which is

great fun. But nothing official.

RS: Any archival CD DVD releases

planned?

AL: Alot of the old stuff comes out, but to be honest I

find that it’s fine for the fans and collectors but alot of

it is not that good. Alot of it is taken from old video tapes.

They remaster it on DVD and to my mind, I don’t know...I don’t

think it’s really worth it myself, some of those old things.

Some of ‘em are good, some of ‘em are not. It seems to me

there’s no quality control on it. People get hold on...old

TV shows I did in the ‘70s suddenly start turning up on DVD.

They’ve got no contracts to release that stuff on DVD. (laughter)

It gets done anyway. They do it and say, ‘okay, well sue us.’

And there’s no quality at all. No matter how bad it is, they’ll

put it out. So I’m not that keen. The DVD market to me

is...everybody’s cashing in on a wave at the moment and

there’s alot of crap coming out. I could have recorded the

Albert Hall live for DVD, but to be honest, when I do a gig to

me, what’s special about a gig is the notes I play, the

songs I do, the feels I have...they’re there for the moment

and they’re gone and that’s special y’know? And once I’m

aware that something’s being taped or recorded, it’s a

whole different ball game. You’re playing something that you’re

going to have to listen back to again and again. And so you

play more safe and you play with a different attitude. I don’t

like that to get between me and the audience. I like to play

to the audience. So I chose not to do that at the Albert Hall.

It’s kind of a shame we didn’t get that gig on, ‘cause

it was really good, but I’m kind of a purist when it comes

to gigs. I just want the gig for the gig’s sake. I don’t

want the audience to have to sit there watching these guys

with cameras squabbling around, the little guy following him

holding the cable. That, to me is a bit of an insult to the

audience. Also, when I play, as I say, I want to play live and

it’s there for the moment. And I hate these bootlegs. You go

and do a show and you think, ‘that was great’ and then a

bootleg of it turns up and it’s not meant to listen to. It’s

a show, an experience that you actually are at. It’s the

audio of it only. It doesn’t usually work as well.

RS: So Arnie says you’re

planning to come back to the East Coast?

AL: Oh yeah, I intend to move all over the States, when I

get there.

there.

RS: Who’s in your band right

now?

AL: Well, I’ve got this band I work with, which is

Richard Newman on drums, which Tony Newman’s son. He’s a

drummer in Nashville now but originally was with Sounds

Incorporated in England. And of course Pete Pritchard on the

bass, who was on the Scotty album. But I was going to play

with The Blasters when I came to L.A. but that was just for

these three club dates, just a little kind of adventure rather

than a tour. I like The Blasters, they’re a good band.

RS: Yeah, I can’t wait to speak

with Scotty about the album.

AL: It’d be nice to tie in Scotty’s comments with mine

about the album. Because I’m really proud of this album. To

me, it’s a rhythm section thing and I just love it as it is.

It’s natural, it’s pure it’s kind of minimalism and that’s

what I wanted to do.

RS: And it couldn’t have come at

a better time, with the 50th Anniversary of rock and roll.

AL: (laughter) I hadn’t even thought about that! It just

took me that long to get it together! (laughter) It’s full

circle for me, ‘cause I’m back to my roots and kiss the

ground I started on. And as I say, I really loved every minute

of it.

RS: Scotty is one of the unsung

heroes of rock and roll.

AL: Absolutely. Personally I think the Elvis Presley fans

base should give him a million quid for every guitar solo he

ever recorded. I think those guitar solos were as important as

the songs. More important, some of them. Everybody’s done

“Rip It Up” and everybody’s done “Shake, Rattle &

Roll” but nobody’d done solos like that in them except

Scotty. And if he never does anything else, that’s good

enough for me! (laughter)

RS: I guess the main thing is to

keep it varied because you’ve done so many great things over

the years.

AL: It’s a matter of getting yourself motivated and

excited. If somebody says, ‘let’s go make an album. I’ve

got a few songs’, I think ‘no, not really’ (laughter)

but if somebody says, let’s go to Peru and put a band

together, I’ll go ‘Now, you’re talking!’ It’s kind

of getting yourself motivated. Getting to put my flamenco

guitar down and go and do some real work!

RS: The flamenco thing still

sounds interesting.

AL: There’s alot of that happening here actually. It’s

strange enough that flamenco players can’t play...I mean, I

saw a flamenco band try and play blues the other night and it

was pitiful! It’s weird, they can’t do it. It’s strange,

isn’t it? They’ve got all that passion and all that

feeling in their fingers for flamenco but when they put their

acoustic guitars down and picked up the electrics (laughter)

they played this dreadful blues. Sounded like a pop band.

RS: Actually I just wrote liner

notes for a new DVD that’s coming out from The Moody Blues.

AL: Oh, yeah. I remember, I used to do lots of gigs with

The Moodies, around the ‘70s, yeah...

RS: ‘Cause you guys were on the

same label, Deram.

AL: That’s right Deram, yeah.

RS: I was always interested in how

Ten Years After got signed to Deram.

AL: It was just our very first record deal. I think it was

actually Decca we were talking to. Decca had London Records,

Deram Records...just kind of names within the Decca label. It

was the first major record company that offered us a contract.

It was very early days in those days. Those days, your first

record deal, they said, ‘you want to sign a record contract?’

we said, ‘Yes!’ They said, ‘wait a minute, we haven’t

told you what the deal is yet’, we said, ‘it doesn’t

matter!’ (laughter) ‘It’ doesn’t matter, we just wanna

get our record out.’ I think we were getting about six

percent of the take on the earliest thing, but it got a bit

better later on. The Stones and John Mayall were on London

Records, weren’t they? In America. But then again, so was

Engelbert Humperdinck, Tom Jones and...Mantovani! (laughter)

RS: And also David Bowie was on

Deram in the early days.

AL: That’s right, yeah.

RS: And also Cat Stevens...

AL: It’s funny, at Decca...and Deram Records...they kept

having Mantovani months and things like that. And all the guys

that worked at the record company, they were all in an older

age bracket. We were like these young, rebellious, upstarts

coming in making strange records and they didn’t know quite

what to make of us...till they started to move a few units,

then they liked it. (laughter)

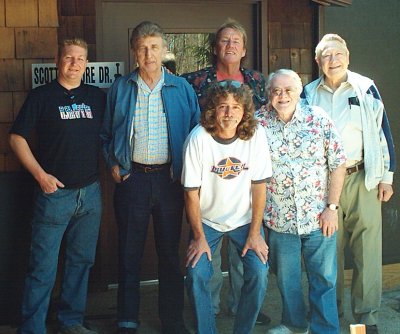

Pete Pritchard, Willie Rainsford, D.J. Fontana, Alvin Lee, Gail and Scotty

April 2003

|